"Our people don't buy local books," she said.

February 15, 2026 - Reading time: 7 minutes

Over the past few months, I have been on a mission to immerse myself in more African literature. This journey began one day as I was going down my TBR (to be read) list, and I realised all the listed books were similar. Similar in the sense of the same language, structure, prose and writing style. After I finally chose my next book and began reading the first page, it felt too familiar. Like I was reading the same book again, just with a different title and cover. I realised then that I had become too comfortable with the predictable plot structures and simple, but engaging prose of mainstream bestselling authors.

Don’t get me wrong; writers like Colleen Hoover or Alex Michaelidis deserve their success—I couldn’t put down Verity or The Silent Patient. However, I found myself craving different voices, bolder styles, and perspectives on unfamiliar tropes.

The Turning Point

In late 2025, I picked up Tomorrow Died Yesterday by Chimeka Garricks. A sense of satisfaction immediately gripped me, a feeling I hadn’t felt in months. The writing was refreshing. It wasn’t difficult to imagine the heat of Nigeria; I knew it. I could taste the flavours of the food mentioned in the book, and I could see the landscapes clearly. I easily connected with the protagonists’ struggles and aspirations. This book made me realise how much I had been longing for something that was simultaneously different from the global mainstream, yet familiar and relatable. From then, I was on a hunt for stories that reflected my own reality.

Warm snow?

As a child, I looked forward to the standard Christmas that we all know today: a brightly decorated spruce tree covered in flashing multi-coloured lights and sparkling tinsel, and I relied on my wild imagination to envision a grizzly man in a heavy red wool suit and snow boots, prancing through icy skies, bringing me presents I had written him letters about. In Southern Africa, the concept of Father Christmas (as we call him) is improbable and almost comical. Most men don't sport thick beards—it’s simply too hot—and Father Christmas and his reindeer would likely collapse from heatstroke in the December sun. As an adult, I think a traditionally decorated tree looks absurdly out of place in a room, bright with rays of sunshine pouring through the windows. In contrast to the sunshine, the decorations look pale, and the flickering lights are almost invisible.

As a child, I would have enjoyed reading more stories that reflected my lived experiences. One example would be books that captured the essence of an African Christmas: the sun high in the sky, a morning church service, and the smoky aroma of seasoned beef and chicken on the grill. I would have benefited from reading about children like me laughing and running around, dressed in cool summer clothes, mouths and fingers sticky with mazhanje and mango juice, their parents, aunts and uncles singing and dancing to upbeat music, ice-cold, refreshing drinks in their hands.

Photo by Duminda Perera on Unsplash

While I appreciate the importance of reading foreign literature for education and as a form of escapism, there is disproportionate exposure to local and regional books. As children, most of us spent so much time reading about other realities and contexts than we did reading about our own. I don't mean to undermine the influence of great children’s authors like JK Rowling, Enid Blyton, Rudyard Kipling, C.S Lewis or Roald Dahl, who played important roles in shaping many of our young minds, but I am also grateful for rising voices like Nomsa Mlambo, author of A Dancing Night and Tafadzwa Taruvinga, author of Yeukai Sadza and Samp, who are writing Zimbabwean children’s literature from familiar, relatable perspectives.

The Books We Aren’t Reading

Despite such local talents, there is an inherent, often unconscious, undermining of local African storytellers. The publishing world has changed a lot over the decades. Gifted writers are frequently forced into the gruelling world of self-publishing because traditional publishing, much like an entry-level job requiring five years of experience, often requires an impressive networking chain or a literary agent to vouch for you, because you can’t do it yourself or let your work speak for itself.

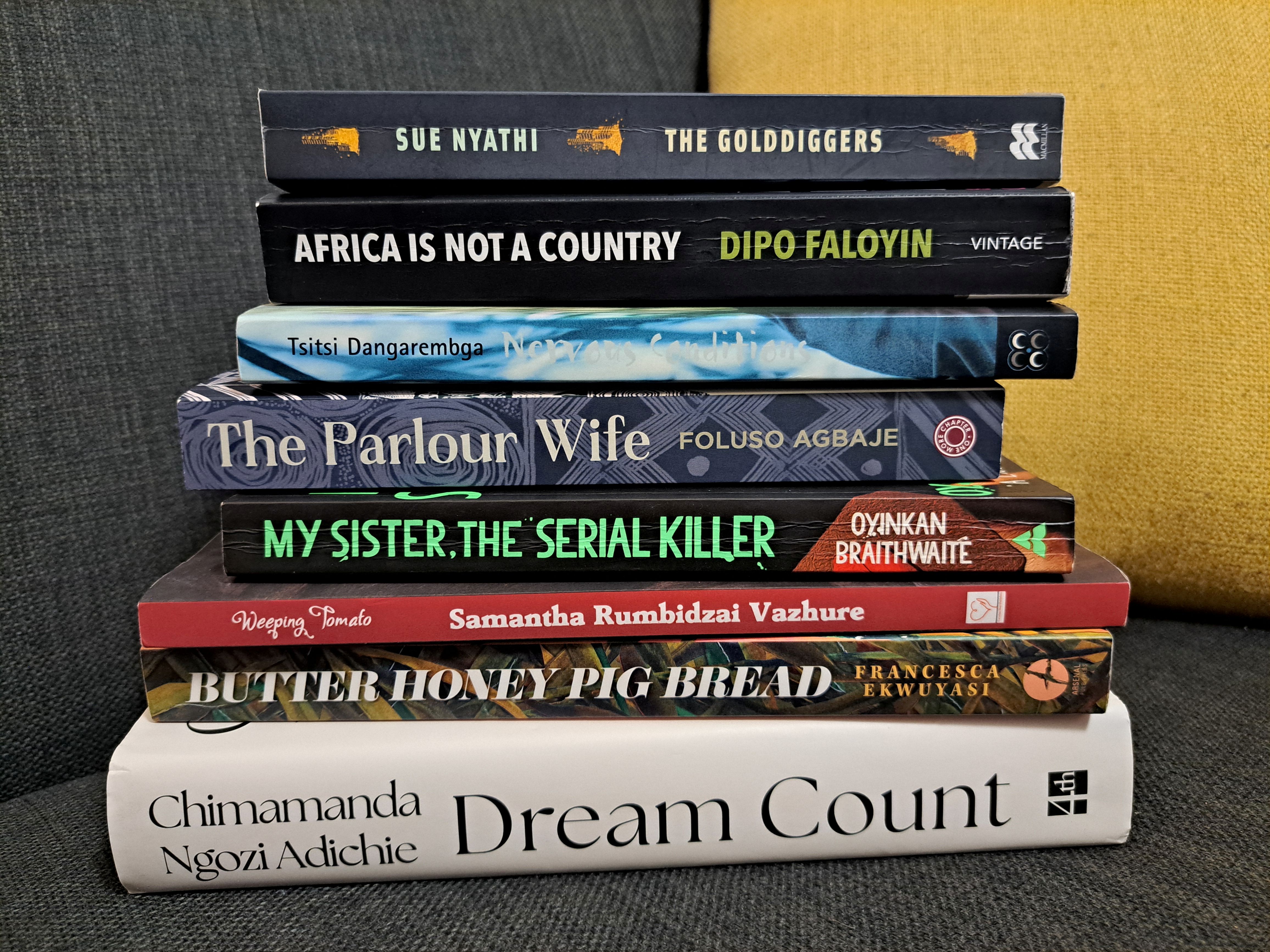

We all know the great African literature giants— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Chinua Achebe and Tsitsi Dangarembga, but a quick search for "African writers" will show you how rich the literary space is.

The Bookstore Dilemma

My shifted perspective has undoubtedly been sparked by my recent experiences after I self-published my own work. While visiting bookshops in Zimbabwe recently, a store owner told me something that stung: "Our people don’t buy local books."

But why? I suppose one explanation is the same reason we choose established eateries over new, independent restaurants: we usually stick with what is familiar. Unfortunately, in the case of books, this has been to the detriment of local writers.

We had a long discussion and attributed part of the problem to the lacklustre literary sector in the country, when many creative, aspiring writers simply do not have the platforms to share and showcase their work. New writers have had to adapt to marketing on social media.

However, the bookstores themselves are part of the problem. Upon entering, I was immediately greeted by Prince Harry. His memoir was the centrepiece of the shop, captivatingly displayed, one book artistically stacked on another. His face was so recognisable that the title was almost unnecessary. I understood why his book was placed where it was; drama sells, and bookshops need to make money. But it was disheartening to see the imbalance as local literature sat tucked away in the back, shadowed by stacks of Harlan Coben, John Grisham, and Freida McFadden books. Even Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s latest, Dream Count, felt like an outlier in a sea of Western imports. I have seen firsthand how difficult it is to break into the market and to be read, and it's even more challenging when international bestsellers continue to be prioritised, regardless of the season, leaving brilliant local voices tucked away in the back of the store - if they are so lucky.

A Way Forward?

The frustrating reality is, at home, readers are more likely to pick up Stephen King’s latest book than they are to buy a book with a familiar-sounding name, unless there is a reason to; either they have background information on the author, or it was recommended to them.

A small restaurant will never grow to become popular unless the community supports it. Similarly, we need a collective shift in attitude towards locally written books. We must stop evading homegrown literature or see it as a sales risk. Our stories — fiction and non-fiction — are being told, and we must be the ones to read them, buy them, and champion them.